This post has many links to beautiful book cover art, such as the Joubert painting on this page, all found on two SF databases on the Web. To enjoy the work on a desktop computer, we recommend you CLICK HERE to open a new tab then pull the tab out of the window and place it next to the article. The images will refresh as you click them from within the article text!

Woolgathering on Cover Art

by Jean Asselin, Editor-In-Chief

“When I was a kiiid…”

…printed SF had yet to thoroughly invade visual media (comics being the exception, another story for another time). There were definite advantages to this general paucity: movie actors played in front of mattes more believable than many a 3D render, and distractinteresting music underscores made TV’s styrofoam sets less noticeable. We children also play-acted using that long lost breed, the generic toy—that is, toys not linked to an existing property like a movie. (Oh, how I wish I’d written down the tales of my 4-inch moulded plastic astronauts lost in the alien architecture of my grandmother’s living-room!)

Anyway, the illustrations that came the way of isolated SF fans were few and far between—the same went for the French-language comics on which I was raised. (I told you this is for another time!) Which left my thirst for SF visuals latch onto the only source available: book covers.

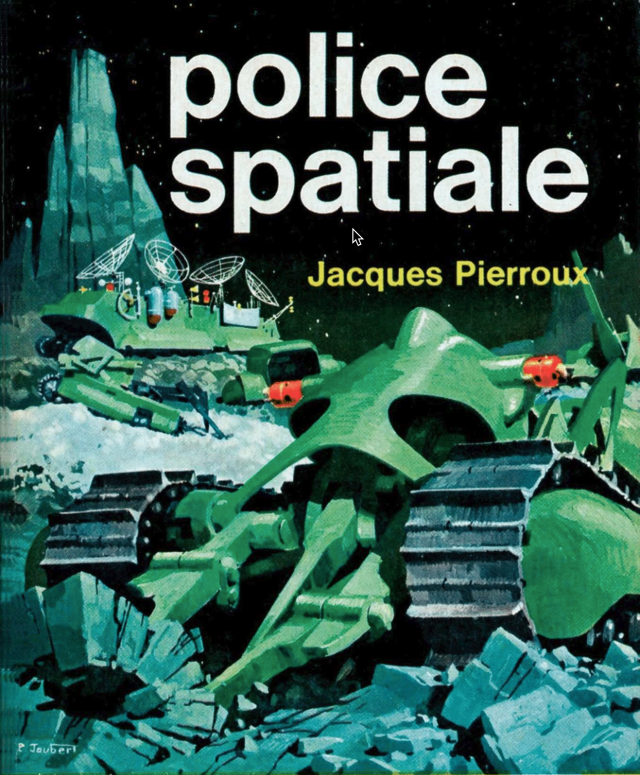

True, a lot of the Doubleday book club cover designs left me cold, but The Last Hurrah of the Golden Horde had me dreaming for some time, likewise paperbacks such as Giants Unleashed and many a Paul Lehr painting such as for Earth Is Room Enough. Trained as I was on young reader novels the cover of which illustrated a scene, especially the gouache art from Pierre Joubert, such as The Dinosaur Hunters, Interstellar Traffic, and Thwarting the Vegans (not animal-food-averse humans, rather beings from the star Vega), the SF Book Club and paperbacks revealed that other approaches were of interest, and I was on the hunt.

Much like how one defines “old movies” versus “new” (anything released before you paid to see them with your own pocket money is old), cover art’s relative age depends on who is working the first time you notice such. Or to quote the famous Peter Graham aphorism, “The Golden Age of science fiction is twelve”: that magical time when you first discover it.

For those who found SF in its early magazines from the late ‘20s—such as our namesake James E. Gunn might have—chances are their favourite artist is Frank R. Paul. To later finds correspond later artists, for instance Virgil Finlay and Kelly Freas. Later still, when paperback books became the main vehicle for SF, you find Stanley Meltzoff, Jack Gaughan, and Ed Emswhiller.

Cover art has its pitfalls, like any artistic enterprise. Not everyone is a Syd Mead, and many a futuristic transport was based on what happened to be contemporary at the time, as with Poul Anderson’s The High Crusade, in which the aliens show up on Earth in a vessel that suspiciously resembles an Atlas rocket.

Done well, cover art can enhance a story with surprising effectiveness. In the case of Ursula Le Guin’s classic The Left Hand of Darkness, Diane and Leo Dillon adopted the “less is more” philosophy that echoes many aspects of the novel.

Modernizing covers for older titles is of course a thing. According to the SF Encyclopedia, John Berkey’s first commissioned cover was for the Heinlein juvenile Starman Jones, which compare interestingly to Clifford Geary’s original with its Tales of the Gold Monkey vibe.

Many of the great SF artists were classically trained and started out with more or less representational imagery, for example Richard Powers. So did Paul Lehr—who would return to it sometimes, as for this Margaret St.Clair title. But both came to dominate the covers of the 60s and 70s by distancing their work from representation, Powers with a surrealist style exemplified in titles for William Tenn or Arthur C. Clarke and Lehr for his juxtaposition of egg-shaped objects over often near-monochrome scenery, as exmplified by these titles from Jack Williamson, and Philip K. Dick, or the two Null-A novels of A. E. Van Vogt: The World of Null-A and The Players of Null-A.

Artwork as the snapshot of a scene can still prove potent, to wit one of Rick Sternbach’s for Larry Niven’s Known Space, and Jim Burns for John Varley’s first collection or David Brin’s second Uplift novel.

The same applies to Michael Whelan’s work on Julian May’s Pliocene Exile—The Many Colored Land and The Golden Torc—or for C.J. Cherryh’s Chanur series, Chanur’s Venture and Chanur’s Homecoming.

Yet, James Gunn teaches that “A title should elevate the story”, and the same goes for cover art: beauty is often found in an illustration that resonates with the tale while taking it farther than the mere title suggests. Gene Szafran’s art graced the novels of such SF luminaries as Eric Frank Russell, Robert A. Heinlein, and Robert Silverberg.

You can tell from the dates on these links that my Golden Age for SF cover art is located somewhere between the 70s and the 90s. After which I spent several years rather far away from English-language libraries, so while I attempted to have a normal life, cover art evolved until, well…. The current issue of Locus Magazine reveals covers that could conceivably advertise any novel in any genre. It would seem that while I napped, the field was taken over by designers who produce great designs for sure but where commissioned art has become a rarity.

“When I was a kiiid…” LOL

Laughter because I’ve now lived long enough to know some trends are on a pendulum, so there is hope for covers where the artwork takes precedence over design.

Granted that sometimes illustrations should be abstract, or bear only a distant relation to the contents of the book. Here are fine examples of the latter, one from the great Jeff Jones, another from contemporary artist John Harris for a collection of stories from James Tiptree Jr., aka Alice Sheldon.

To me, the best cover art will always be those that manage to evoke the story without overstepping its contents. Which is what we aim for when we choose imagery to accompany the fiction and poetry published at James Gunn’s Ad Astra.

Leave A Comment