We Turn Out Okay

by Cooper Tamayo

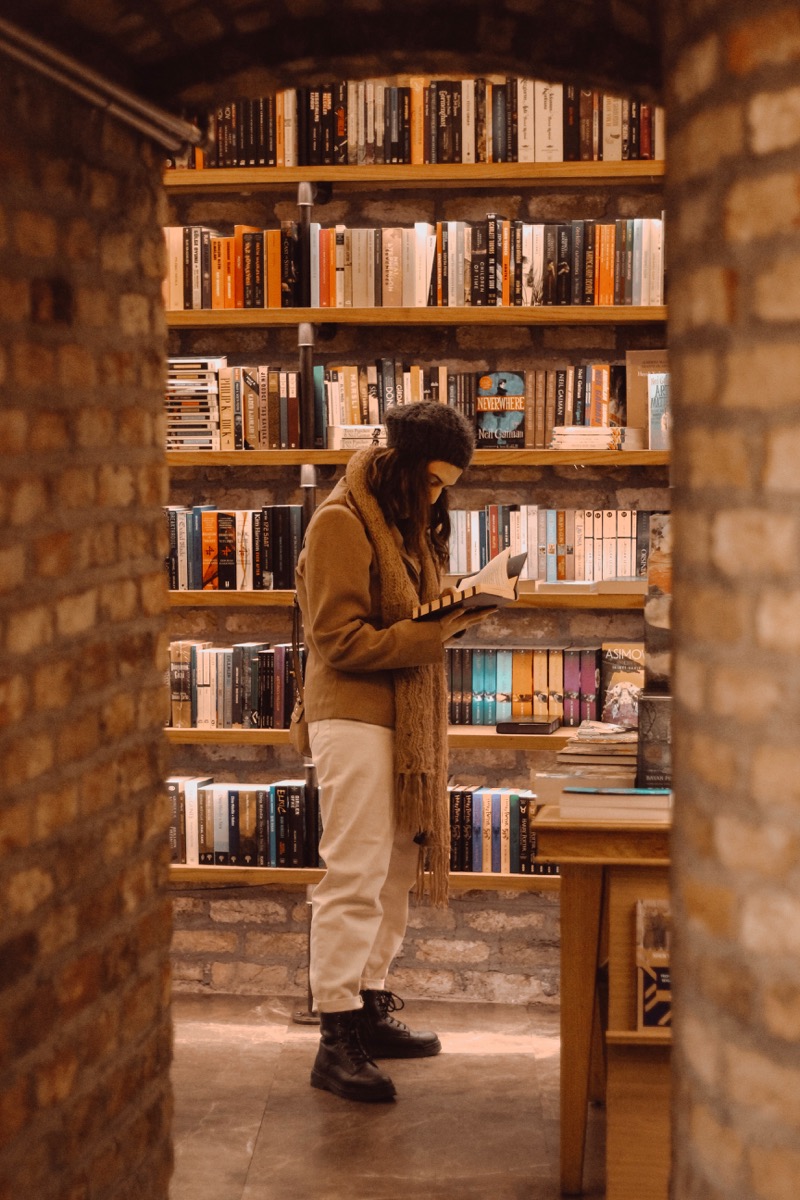

Photo by Hümâ H Yardım

Photo by Hümâ H Yardım I woke, curled and alone on a rumbling dark bus, remembering someone I’d done my best to forget. Remembering the Other Me.

It had been a long, cold day. A double-socks, leggings-under-jeans kind of day. You couldn’t stay outside more than a few minutes without feeling like you’d lose some extremity or patch of skin to the cold.

I was running away from home.

Dad had left, I figured I might as well too. Part of me blamed Mom for our family’s dissolution, part of me believed she’d have it easier without me. That secretly she wanted me to go. So, I boarded a midnight bus with some clothes, some cash, and no plan except to find a waitressing job far away and work until I figured out what else to do with my life.

It was one of those musty Greyhound buses: broken outlets beneath seats upholstered to look like a child’s forgotten birthday party. Warmer inside than out, but not by much. I sat alone in the almost-back row, hugging the backpack that held everything I would start my life with, and resting my head against the window, my breath fogging the outside world, so it was that much harder to look back at what I was leaving behind. Forever, I imagined. I closed my eyes.

Sometime in the night I woke up, remembering.

It happened the spring before I ran away. I’d been walking in circles around our local used bookshop, sniffling pollen and looking for nothing in particular, when I saw a woman who looked too much like me. I stared. She seemed older than me, mid-twenties maybe. Her hair was longer, her skin clearer. But she had my face—her eyebrows were mine; her posture was mine. The longer I stared the more uncanny it became, like watching a home video. Then she looked up, right at me staring, and smiled.

I fled.

She caught me later, crossing the street as I made for home. She bumped my shoulder as she passed. I met her eyes. Up close there was something off about her, backwards. Her freckle was on the wrong cheek. No, she just wasn’t the mirror version of me I’m so used to.

“Don’t worry,” she said, “we turn out okay.” She smiled again, like we shared a secret, then moved on with the crowd. “Just remember to look out for each other,” she called before she disappeared. That was the first incident.

I thought about her, about we turn out okay, nonstop for a week. But eventually I decided it was just a weird coincidence and a joke. If I ran into some teenage brat who kind of looked like me, I could do the same thing to them. Say don’t screw this up for us, or maybe beware the man in black, to really mess with them. Or hand them a slip of paper, say these are your numbers, then slip away. I told some people the story, they laughed, then I stopped thinking about it, pretended to myself it had never even happened.

Alone that night on the bus I played the incident over and over in my mind. Maybe it meant that I would be fine, land on my feet, turn into one of those high-school-dropout success stories. But the truth was it wouldn’t really be okay without a family. Look out for each other had to mean more than just me.

Mom picked me up at the bus station the next morning and dropped me off in time for school. She picked me up at the end of the day too, and I’ve never fully appreciated that, I think.

The second incident came six years later. I had a shitty research assistant position, my first one after college, at a biomedical lab in Boston. I hated harvesting the mice, raising them and killing them every other week. I hated working in the basement in the dark alone. I hated my PI, and he hated me. Though maybe that was never true. There were a lot of people I thought either hated me or saw that I was incompetent when maybe none of them ever did and maybe really, I wasn’t.

I was about to be fired, I thought, and I wanted to quit to get ahead of it. Serve coffee or something while I figured out next steps.

She sat on a park bench with a book on her lap, watching the ducks drift in clumps across a muddy, reedy, mossy pond. She kept glancing up, tracking them as they passed like she suspected they might try something. Come at her from the sides like velociraptors. I don’t trust birds either.

I slowed my jogging to a walk. She looked up without surprise and nodded me closer. Older now, though so was I. But the eyebrows, the freckle, were all the same. She was wrapped in a thick gray coat. I didn’t recognize it, but her shoes were something I might have worn. I stared, standing close enough to shake her hand, read her book.

“You’re thinking of running away again,” she said.

“No.”

“No?”

“No.” What was the point of lying to yourself, I wondered.

She looked me up and down, then pretended to go back to her book. “Then I guess there’s nothing we need to talk about.”

I was suddenly annoyed with her and her coy attitude, like I was supposed to be enamored with the whole situation. “Who are you?”

She sighed, sucked air through her nose as if I was the one trying her patience. “Whatever I say, it will be something you’ve already thought about and something you won’t really believe.”

“But, you are the same person…”

“From Last Chance Books? Yes. What was that, five, six years ago now?” She squinted up at me, the sun bright on her face. “You look good.”

“Thanks. You’re, what, you’re supposed to be me?”

“I am you,” she said. “Or I was. You’ll be me, eventually.” She held out her arms in a like-what-you-see? kind of way. She looked tired. “How’s Mom?”

“She’s fine. Look, I have to go.” I was done, caught between embarrassed and scared and irritated. Not wanting to believe any of it and not finding a way to forget it all either. Pretending to be in on the joke while underneath I had no idea.

She nodded a goodbye like we’d had an entirely normal pondside chat. My feet stuck in place.

“Should I stay with this lab?” I asked.

“That’s up to you,” she said, “but you’re better there than you give yourself credit for.”

“I’m not.”

She shrugged. “You asked. That’s my answer.” She went back to her book.

I jogged away, avoiding the ducks and trying hard not to look back.

I stayed with the lab. Two years later I was lead author on a paper about heritable immunities in mice, and co-author on two more. I left to pursue a Master of Public Health at Boston University. That’s where I met Val, a doctoral candidate in anthropology. She studied death and exorcism and wore soft, plum purple lipstick. She was the coolest person I’d ever meet. We married in the springtime, when my allergies and her enormous family did their best to turn the day into chaos. But Mom was there, delivering antihistamines and vanloads of new in-laws wherever they needed to go. I kept expecting an uninvited guest to make an appearance, someone sitting in a back row with a quiet, knowing smile, but none came and that was okay. Val was gorgeous and I was so happy it hurt.

We adopted a cat and later, after Val landed a permanent teaching position, a little girl. Rosie’s first word was ‘bubble,’ she has a pet mouse named Mousy, she hates the color yellow and the taste of peanut butter. She plans to become either a submarine captain or a professional harpist, though neither of her parents have ever so much as plucked a musical instrument. She is and will always be perfect, and she is growing up so fast that I cry about it alone sometimes. I tell Val it’s because I’ve been thinking about endangered animals and refugee children. She pretends to believe me.

One cold day at the edge of November, I took a cab home from City Hall. I’d been called to give testimony to a health and safety committee about my work on socioeconomic determinants of health (read: how much the hand you’re dealt can actually do to you). It was one of those bad-faith affairs where one side just wants to wag their fingers at you for the public record and the other is sorry you had to come here at all. But I said my piece, answered their questions, and wanted now just to curl up at home.

It was a gray day, darker than it should have been mid-afternoon. Rosie and Val were in Sweden for a week-long anthro conference, and I was dulled by the thought of returning to an empty apartment. The cab and its driver both smelled like they hadn’t quite given up smoking, so I rolled my window down and watched thick clouds settling overhead. I wondered if I’d summoned them with my gray mood.

The cab stopped short at a light. A woman crossed the street in front of us. She looked up as she passed and, for the third time, I saw a stranger wearing my face. She seemed not to see me. Just then the first raindrops hit the windshield.

I jumped out of the car, the driver shouting after me about my fare and my briefcase. I ran up behind her and touched her elbow. Her eyes went wide when she saw me and her arms, which had been wrapped tight against the wind, fell to her sides. I moved to embrace her, then hesitated.

“Hi,” I said, as fat globs of rain pattered down around us, “where are you going?”

“Nowhere,” she said. After a pause, “that way.” She waved towards what did seem like nowhere in particular. Heavy, purpling bags drooped under her eyes—I didn’t look like that yet, did I? —her hair was thin, and there were shining silver grays poking out here and there from her head. Her clothes were faded, her nose was red. A trail of snot ran down and around her lip. She wiped it away, shivered, then straightened up.

“You’re doing all right, then?” she said.

“I am, yes. Yes, I wanted to tell you I am.”

She didn’t say anything, but it looked like she wanted to, or was at least considering it. “Are you okay?” I asked.

“I’m fine. It was nice to see you, but I do have to go. Good luck with everything, Lex.” She walked away, head bowed, coat flapping. No one had called me Lex since high school.

“Wait!” When I caught her, she was bent over in a coughing fit, holding out her hand to keep me at a distance. Around us streams of faceless pedestrians were unfurling umbrellas, zipping up coats, hurrying towards home. Gingerly I put my hand on her back.

“I’m fine,” she coughed, “go on, I’m fine.”

A horn blared and we both jumped. My cab driver gave the meter a set of exaggerated taps. I waved and held up the two-minutes fingers.

“Come with me,” I said to myself. She stared, blank and unreadable, the same stare I used to give strangers who approached me in bars, or that I give Val when she asks without warning something hard or scary or emotional. If you’re not patient, you might just say sorry to bother you and leave and never find out what might have happened if you’d stayed.

“I have tea?”

“Okay,” she said, and she gave me her arm and let me pull her into the cab. The driver glanced at us in the rear-view but said nothing. The three of us sat in silence, staring out our respective windows. I wasn’t nervous. I could feel in my gut that this was the right thing to do, and I quietly resolved to follow that feeling as far as it would take me.

Home had the cold that comes from being mostly empty for a week. I flushed it out best I could by turning on every single light. She stood in the doorway, looking a little lost. I showed her to the bathroom and gave her a dry change of clothes, then I put on a pot of hot water. I searched the kitchen, but I’d been ordering out all week and we didn’t have much more than tea. I poured some almonds into a bowl.

I found her in the living room, stepping slowly, reverently, around the clutter. She bent down to look at a framed picture on a side table. “Here,” I handed it to her. She hesitated, then held it tight in both hands. It was a photo of me, Mom, and Rosie picnicking for Rosie’s fourth birthday, her all in pink and Mom all in white, smiling under an enormous sunhat. The sky is blue behind us, and against the grass is the frantic red-yellow blur of a child catching a frisbee.

“Is this…?”

“That’s my daughter, Rosie. She’s bigger now. Six next month.”

“And that’s Mom?” She touched one gentle finger to the glass of the frame.

“Yeah.”

“Mom, is she…”

“She’ll be here for dinner tomorrow, when Val and Rosie get back.”

“I…I…”

When I cry, if it’s not a few quiet tears, it’s slow, loud, gasping sobs that sound like I’m drowning. Other Me cries the same way, and when she did it there in the living room, squeezing an old photograph into one of my lumpy orange sweaters, I did what I always want people to do when I cry: I dropped a blanket over her shoulders, switched out the picture for a pillow, and looked away.

When she calmed down, I gave her tea, quiet chamomile, and I sat us on the couch. Then I said, “You never really knew, did you? How we would turn out?”

She shook her head. “I didn’t know. I just hoped.” A long time passed before she spoke again. “Where I come from, after we ran away, Mom stopped taking care of herself. Then she got sick. Things never really got better after that. I wandered for a while, never settling anywhere long, just surviving. Eventually I wound up here.”

“I’m sorry.”

She looked at me with glistening, bloodshot eyes.

“I didn’t mean to mess with your life,” she said. “Just when I saw you, you looked young enough that I thought maybe I could, I don’t know, steer you just a little bit, without really interfering. I didn’t know what would happen, if it was even safe, but…”

“It’s okay,” I said, taking her hand. “It worked. You helped me.”

She closed her eyes and grimaced, scrunching her face, squeezing back more tears. Val has a picture of me making that same face, from the day we brought Rosie home. It’s hideous. She says it’s perfect.

Other Me opened her eyes and breathed deep. “I went to see Mom once, too,” she said. “I didn’t talk to her, just saw her at the grocery store. Besides that, I tried to stay out of the way, focus on getting home. Nothing has worked, though. And even though I never had anything going for me back there, I can’t seem to stop trying.”

Over the years, I thought I’d imagined every possible explanation for my encounters with the Other Me, all the scenarios, benevolent and sinister and outrageous. I never considered she might be lost.

“You know I went back,” I said, remembering, “to Last Chance, a long time ago. I thought I might need to find younger me. Us. I went back a lot.”

She had never known what would happen to me, where I’d end up. She had never believed in me as much as hoped for me, wished and willed that things might go better for me than they had for her. All the while trying to keep herself away from her only connection to a world she’d fallen into.

“What happened?” she asked.

“Nothing. I bought some books.”

She sipped her tea. We listened to the rain. “That’s good, then,” she said, a little while later. “That’s good.”

We ordered Indian and ate quietly while she flipped through old photo albums. She’d never seen our high school graduation, or my college haircut. She called it ‘a surprising choice’.

She tried to leave after we cleaned up, but I convinced her to stay the night. It was raining, after all. I showed her to our guest-room-slash-home-office. She stood cautiously by the bed but seemed unwilling to get more comfortable until I’d left.

“You don’t need to hide from us anymore,” I said from the doorway, trusting that feeling in my gut.

“What?”

“You could stay. Here, or with Mom. She has more than enough space.”

She shook her head. “I can’t,” she said, “I shouldn’t. I don’t fit here.”

“You should stay. At least until dinner tomorrow. You can meet Rosie.”

She looked at me, in the eyes briefly, then mostly at my shoes.

“We’ll talk about it tomorrow,” I said. Then I closed the door.

I can tell by now when I’m thinking of running away. I made a bed on the couch, so I’d be able to hear the front door open. I was up most of the night, listening, but eventually I dozed. When I woke up, she was gone.

I left in my pajamas and a blue puffy coat. I couldn’t find my slippers, so I threw on Val’s ghastly sea green crocs and ran out into the morning chill before the sun was properly up. I tried to imagine where I would go if I were her, and I had no idea. But I was pretty sure I knew where to start.

I found her on a bench at South Station, waiting for a Greyhound bus. She didn’t look up when I sat beside her.

“Your cat bit me. On the nose.”

“Oh, sorry,” I said. “I think it’s meant to be affectionate.”

She nodded and shrugged. We sat for a moment, listening to the low sloping growl of suitcase wheels passing by.

“Listen, you should stay. We could use another set of hands around here, sometimes, and I know Mom would like having you around. It would mean a lot, to me, if you just met them.”

“This isn’t my life, Lex. Mine’s gone. I’m not a part of yours, and I shouldn’t be. It was nice seeing you again.”

“No, you can’t just leave, you—” it suddenly hurt to speak, “—you…you were there for me. You looked out for me when I wasn’t looking out for myself, and I know no one’s done that for you for a long time, and I can’t imagine what that’s been like, but I…but will you let me do that for you, now? It’s only right. Because we have to. We have to look out for each other.” I paused to sniff and wipe my nose. She didn’t say anything, but she didn’t get up to leave either.

“And I know you’re only mostly me, and I’m mostly you. By now we’ve lived pretty completely different lives. But I think that’s close enough for, well, family.”

We were quiet. A last call for a bus came over the loudspeakers and I hoped and hoped it was hers and she was ignoring it.

“I’ll meet them,” she said softly. “I’ll stay, just for dinner tonight. I don’t want to impose.”

I smiled, still sniffling. “Not at all,” I said. Then, “Thank you.”

“What if I, I don’t know…destabilize reality?”

That one did throw me for a second. “Then we’ll figure that out together. I don’t know what happens to us from here on out, but the most important thing, what you’ve done for me and what I have to do for you, is that we take care of each other. Everything else we’ll do one day at a time.”

“They’ll be scared of me,” she said, looking at her toes.

“So what? They’re already scared of me.”

Finally, she laughed, gave me an actual smile. “Okay,” she said.

I laughed, “Okay.”

Then she gave me her hand and we walked out of the station together, into the morning sun, and turned towards home.

“Oh. We should probably pick up some groceries.”

END

Leave A Comment