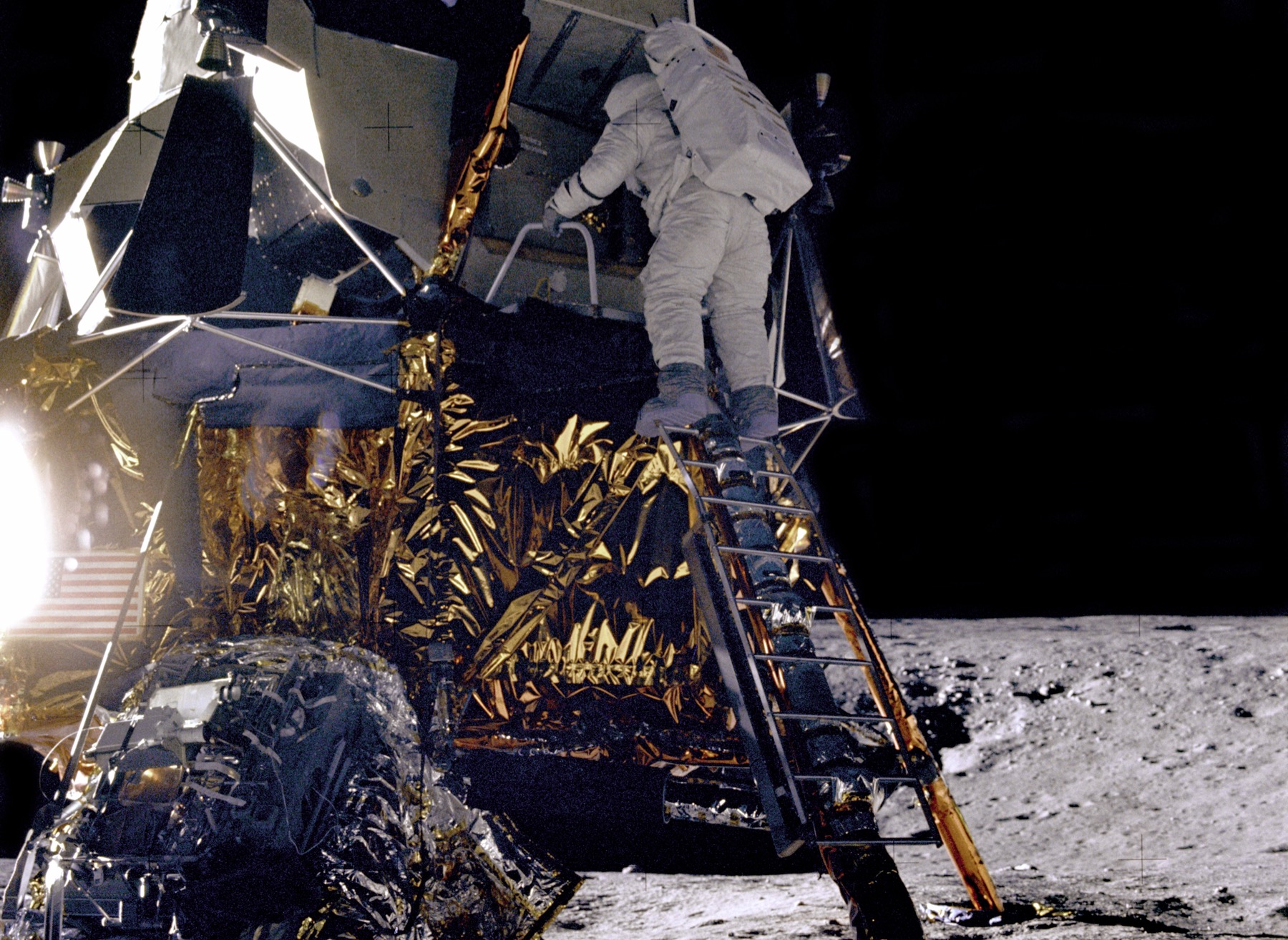

Photo by NASA

The Ancient Astronaut

by Brian D. Hinson

The Lunar Module hatch popped open. Leonard’s boots emerged sole-first as he crawled backwards onto the egress platform. The sun glared against the black velvet sky just above the S-band dish atop my full-scale replica Eagle. Earth was in half-phase to my left, over the long-abandoned ruins of the spaceport. About a dozen or so tourists in tightsuits sat in the bleachers. I stepped back as I watched Leonard, soft radio static hissing, my breathing amplified by the antique refurbished life support system.

“Okay,” came Leonard’s voice over the radio. “Now I want to back up and partially close the hatch. Making sure not to lock it on my way out.”

I laughed my scripted laugh. “That’s a good thought, Buzz.” Leonard was my Buzz, and I watched as he came down the ladder for the 1,000th time. At least. “You’ve got three more steps and then a long one.”

Another voice, my granddaughter Eva, whispered in my helmet on a private freq, “Good, positive feedback from the bleachers so far. A few ‘ahhhs’ when Buzz came out.”

At the last rung on the ladder, standing in the antique space suit I had crafted myself with umbilicals and manual knobs and a bulky life support pack, he looked about, as if nervous to venture further. He dropped down, drifting lightly to the footpad of the landing leg. “Whoa! That was a good step!”

“About a three-footer!” I replied.

Buzz turned and looked at the deep shadows and the broken lunar landscape of Tranquility. “Beautiful view.”

“Isn’t it something?” I said, tinting my voice with awe. “Magnificent sight out here.”

“Magnificent desolation.”

Eva in my ear again, “There’s applause. One teenager’s shitposting. Everyone else is enjoying the show.”

Buzz studied the landing pad and said, “Looks like the secondary strut had a little…a little…” He coughed, rough, weak, and sickly.

Eva suddenly panicked in my ear, “Heartbeat is erratic. I think it’s cardiac arrest!”

Skilled in maneuvering on the lunar surface, unlike Neil so long ago, I dashed toward Leonard in my own antique bloatsuit, as house angel Mora scrolled red text across my visor: GUY, ATTEND TO LEONARD, MEDICAL EMERGENCY.

Leonard wheezed his line, “A little thermal…effects…”

Buzz crumpled in front of the landing leg.

“Get him back in the hut immediately!” Eva’s panic pitched her voice high. “He’s flatlining!”

I made it to him and flipped him over. My own heart raced, thrumming in my ears. With eye movements I keyed the private mic to Eva but the wrong sensor picked up, and now I received a live feed from the audience scrolling on my helmet display.

“Wow! Did one of the astronauts die?”

“No idea. This is exciting!”

“Does he make it? I wish I knew my history.”

“Finally, something actually happened in this boring-ass show.”

I turned Leonard’s O2 to max and pumped his chest, trying to get his heart going. Lugging him back to the hut would take twenty minutes, even if someone in the crowd assisted.

“Still nothing.” cried Eva.

Leonard was gone. My friend, my colleague, died in the middle of an act. If an actor’s time comes, the best possible moment is to die after the applause, the cheers, the smiles and tears following a solid performance. After the bow. He didn’t quite make it.

There’s another showbiz cliché that fits about right here. And I wasn’t going to let him down. Leonard would rather have died than screw a scene. I needed to keep my shit together just a few more minutes.

“Buzz! Buzz! Talk to me!” As I kept pumping Leonard’s chest, I keyed some of Eva’s words, ran it through the radio static filter and broadcast it to the audience.

“Get him back! He’s flatlining!”

“Roger, Houston,” I replied.

Clumsily, I hefted Leonard and his bulky suit over my shoulder in a fireman carry. Getting up that ladder like this was going to be a trick. This was risky improvisational stage acrobatics. Dropping him would ruin everything.

“What are you doing?” screamed Eva in my ear.

I closed her channel.

“We’re gonna make it, Buzz. Hang on. Hang in there.”

There were some things in my favor. That last rung was only two feet from the surface, not the historical three. The hatch was a bit larger than the original on the Eagle, and our life support packs somewhat smaller, refurbbed with a lot of modern gear. I could stick his inert form through the hatch without too much effort, if I could only get him all the way up.

I balanced Leonard as best I could on my shoulder with my left, grabbed a rung with my right hand, gripping as tightly as possible in these nearly inflexible gloves, and pulled as I jumped. My right foot made it to that bottom rung and I felt Leonard’s helmet bang against the side rail. Step by shaky step I climbed. My heart dropped through my boots when Leonard slipped incrementally, but I braced him against the ladder. Straightening out, I made it to the egress platform, placed the top half of his body there, and pinned him as I crawled over to reach the hatch. “I’ve got him at the porch, Houston, I’m opening the hatch.”

“Roger.” That’s the best I could do at improvising Houston’s response with an audio clip of Eva.

With the hatch open, I climbed back over him, turned around to get my feet on a ladder rung. As I wrestled Leonard through, the feed kept scrolling.

“Sooooo glad I stopped for this reenactment!”

“For an amateur side-show this is really well done!”

“Rooting for you, Buzz!”

With Leonard inside the lander, I followed on my hands and knees, just like the old Apollo guys. Closing the hatch, I radioed Houston, “I’m pressurizing the Eagle. As soon as we got pressure I’ll attempt to revive Buzz by forcing pure oxygen and more CPR!”

The act didn’t go on too far from there. The cameras in the cockpit fed to the helmet receivers of the audience. I kept pumping Buzz’s chest as I waited for the pressure to build enough to remove his helmet. Thing is, this replica didn’t pressurize. As I counted a few more beats, I cut the feeds with static, but amped it as an audio-play. I got Buzz to breathing, replayed his coughs, and reveled in the accolades from the audience text scroll. I fired the gas cannisters to blow dust, simulating the launch to rendezvous with the Columbia in lunar orbit.

We hadn’t had this level of raves since…well, we never had such raves.

I didn’t open the hatch for a bow. If Leonard couldn’t take one, neither would I.

I couldn’t anyway. Sobs, delayed by sheer will until curtain, overtook me. Kneeling beside Leonard, I wept.

Eva, my granddaughter, waited for me as I cycled through the airlock, eyes red from crying and that vein in her temple pulsing. “You sick fuck! What the hell?” She fumed in her autochair, her thin, inert legs in pajama pants, arms crossed, face flushed.

“I’m sorry,” my voice unsteady. “But—”

“Bullshit.”

I stood there with my dead friend in my arms, both of us still in our suits, me with my helmet off. I waited. She was blocking the way.

“This stunt proves, proves beyond any doubt whatsoever, that you’re a carnival slimeball. A scumbag. He was your friend.”

Softly, I replied, “Yes. And he was yours. I know this is—”

“Oh, God, Gramp!” Her knuckles were white as she gripped the chair arms, as if preparing an impossible leap up. “Using him as a prop just to make money when he needed help? You’re a murderer.”

“Whoa, now. Hold on—”

“Murderer.”

“Are you going to let us in?”

Blind with grief and anger, she just now noticed that I was cradling Leonard’s body in the deflated suit, his helmeted head resting on my shoulder.

“Leonard…” Her expression crumpled and her lip quivered. She scowled, rolled quickly backwards and turned, fleeing. Eva hated for anyone to see her cry.

The roomy equipment vestibule beyond the airlock was lined with racks for suit parts and drawers for tools. I knelt, carefully setting Leonard facedown on the floor. Getting myself out of the damned bloatsuit was priority one, before I could concentrate on Leonard. Usually Eva helped, but today…

Once free, I turned my attention to my friend and removed his boots, gloves, life support pack…and when I rolled him over and unlocked his helmet, a lump reformed in my throat. My words managed to swim around it. “It was a good show, right? That last one was the best we ever did. You would have been proud.” I slapped his shoulder. “We got a perfect score with extra accolade points. And the cash tributes! Why didn’t we think of this before, eh? No one cares for the real history. You said so, yourself.”

He was old. Leonard had more wrinkles than hair. He had lived and lived well, the boom and bust life of an actor. Eventually he had settled into the Buzz character. I had leased a spot of land outside the ruins of Port Armstrong, Luna’s first dedicated spaceport, now a UNESCO site. A micro-rail line ran train service to the ruins three times a week from New Cairo. Our shows were timed with the tours and we lured whomever we could to walk an extra hundred meters for an historical reenactment. They sure didn’t do that at the real Apollo 11 site. And if they did, Leonard and I would have done it better.

Now, no more Leonard.

I smiled through the sadness. “We had some good times, eh?”

The buzz of Eva’s autochair drew near. I tensed. I couldn’t weather another blast of venom. I refused to look up as she rolled in.

Silence was not what I expected.

I busied myself separating the upper and lower torso suit components, carefully sliding the upper from his body, leaving him on the floor with his arms above his head. As I placed the torso section on the shelf, Eva spoke, her voice cracking. “What are we going to do?”

I still didn’t meet her eyes. I stared down at my friend. “We’ll find something to wrap the body and—”

“No. I know that. What are we going to do?”

I didn’t want to think about the business right now, a future without Leonard. But Eva was right. We had to. “We find a new Buzz as soon as we can.”

The screen in the living area of our converted maintenance hut showed the man interviewing for the role of Buzz Aldrin. Eva and I leaned forward from a worn floral-print couch. Petrus looked nothing like Buzz, but that didn’t matter, Leonard didn’t, either. Only historians knew what Buzz looked like. This guy was a handsome fella, young, African descent, very strong voice. The voice part was essential. We broadcast static over the comms for authenticity.

“Are you familiar with the Apollo landings?” I asked.

“Truthfully, all I know is the basics. There’s a script, right?”

“Of course,” I replied. “I was wondering about your interest in working this show.”

“I love history. Your costuming and set look great, by the way.”

I groused privately to Eva, mic muted, “He’s ass-kissing. He’d know what the set should really look like if he had an interest in Apollo.”

“That doesn’t mean he can’t appreciate that everything looks really awesome,” she replied. To Petrus, she transmitted, “We loved the soliloquy you sent.”

Petrus smiled. “Thank you. I wish that play would have run longer.”

I knew what he meant. As little as acting paid, it was always better than a stretch with no gigs. “Space is limited here. We’ll have three living in a small refurb.”

“How much is rent?”

“No rent,” I replied. “The space is free and our Buzz gets a 10% cut from every performance.”

“Sounds good.”

Again, he beamed that practiced actor’s smile. I cut my eyes to Eva. She was eating this up. Her hand went up to her shortish blonde hair, a quick stray check as she returned the smile.

Petrus dropped his grin for a serious question. “I do have concerns about the safety of that antique suit.” Normal. Apollo-era suits swelled from internal pressure. On the first space walk, Leonov had to bleed off oxygen to dangerously low levels just to re-enter the Voskhod spacecraft.

Eva took that one. “Guy here is a master of ancient space suit craft. He’s been wearing the same Armstrong suit in all shows for the last nine years. They’re not comfortable, but we run checks beforehand every time. It takes a while, but we don’t cut any corners.”

“Did your last man go on to greater things?”

“He sure did,” I said, nodding.

Now laughing a friendly, faux laugh, Petrus said, “Good enough for me. So, if you folks like me, when will I hear back?”

“Hold on.” I blanked the video and audio feed from our end. The other interviewees were less than stellar. This guy Petrus looked solid. Good acting chops, friendly demeanor. That last bit was actually more important since he’d be living here.

“I like him,” said Eva.

“He’s not bad.”

Eva produced a half-frown. “So…you like someone else better?”

She knew I didn’t, and shows were being cancelled. “You go ahead and give him the news. And make sure he knows this is a thirty-day trial. No contract ‘til after that.”

Being a tourist trap doesn’t mean we don’t have standards. A lot of our great net reviews come from us flying above the low expectations.

Petrus over-acted in the first rehearsal in the living room. Eva noticed, I could tell by her lips set in a straight line; her eyes only leaving her script palette to throw a worried glance my way. He wasn’t untalented; he simply thought that was expected. I sat him down and explained what we do here, what we really try to do. We reach for the stars, we bring our A-game every time, every performance. We play it straight; we play it right; we play it like there might be an Oscar waiting at the end of the season. And that’s why we search for actors, not just anyone willing to go through the motions for bread and a roof. If we did it B-grade, the bread would disappear, as would the roof. And the air.

Petrus apologized and excused himself to Leonard’s old room, now his. “I need a moment.”

Eva whispered, “I’m sorry, Gramp. He looked so good before.”

“He’s good.” I patted her hand. “He just doesn’t know what we want.” We both looked to his bedroom door behind the sofa, Leonard’s old room.

After the funeral we had cleaned it out, stripped it to the cot and the plastic chest-of-drawers. Leonard’s lurid murals of historical vaudeville actors remained: W.C. Fields juggling cigar boxes and Lillian Russell resplendent in a huge 19th century dress. For extra cash above his 20% cut he sold original paintings of contemporary actors. His unsold stock now decorated the walls throughout the hut. Petrus had said he liked the wall art, but he was just being nice.

The door slid open and we quickly turned away. He walked to the front of the sofa, chewing his lower lip, eyes on the script.

“Ready?” I asked.

“I think so. From the top?”

After my curt nod he went for it. When he finished, expectant and hopeful eyes seeking comment, I released the breath I didn’t realize I was holding. Eva’s eyebrows were up and a small grin lit her usual rehearsal poker face.

He was flawless. We applauded.

Two weeks after Petrus’ debut, I was only mildly surprised when both he and Eva emerged from her room for breakfast one morning. I had noticed the flirtations. After I retired for the night, they’d been sharing the sofa and watching a movie. Things obviously hadn’t stayed that way. Eva beamed, humming as she rolled about the kitchen, the aroma of eggs and waffles making my belly growl. Petrus looked a bit sheepish.

After breakfast we suited up for the show. Eva assisted Petrus, being more handsy than usual. She made me feel a little awkward, probably Petrus, too, judging by his anxious smile. Once cleared and outside, I signaled him with the stubby fingers of the old spacesuit: four numbers, then pointed to my antenna. He got it and switched freqs. It would take a minute or so for Eva to discover the new channel and eavesdrop.

“Don’t you break that girl’s heart,” I warned him.

“I truly like Eva, sir.”

“She has a fragile ego with guys. And in that chair, she’s got limited options. And I worry about your intentions.”

“I like Eva. Is there a problem?”

“I don’t know if there is or not. If you make her cry, there’ll be a problem.”

We shuffled a few steps in silence, cresting the small rise. The Eagle came into sight, the sun glinting off its faux gold wrap.

“About her chair,” Petrus started, “why doesn’t she get treatment?”

“Eva didn’t tell you she’s a Purist? The genes she was born with are the genes she dies with. I found her ten years back living on a commune in Hevelius with a bunch of those freaks. She was crawling around dragging her legs. Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia. It started to weaken her legs when she was about twenty. She was already deep into the Purist bullshit, and when her mother tried to force her into a hospital, she took off and joined a damned Purist commune. There were a few dozen there with all kinds of genetic failures, all fucking curable.”

“She never mentioned that.”

“Eva doesn’t want to scare you away. Now she’ll be pissed with me that I said something.”

“Maybe she should be.”

That was a little bold, on top of fucking my granddaughter. “You asked.” I kicked a rock, sending it arcing off into the black sky.

“That doesn’t mean you have to spill her secrets.”

Now I was growling. “If I didn’t tell you the truth then you would have thought I was abusing her by withholding medical treatment.”

“Hmm.”

“What the fuck does that mean?”

“I didn’t mean anything.”

I stopped and flipped up my outer visor, squinting in the harsh sunlight, so he could see my anger, not just hear it. “I look after as best as she’ll let me, right? You make her cry and you’ll be out of a roof and a job. It’s thirty minutes to show time, just get your ass up the ladder and let’s do the goddamned show.”

The fallout from the confidence with Petrus came sooner than expected. The next morning, eggs sizzling on the stove, Eva slapped the silverware down. “You’re a real piece of shitwork, you know.”

Of course, I had to be certain what meant. “What now?”

“Like you don’t know. You told Petrus I’m a Purist.”

“Well, if you’re embarrassed by it—”

“No. That’s not it. It was the commune I lived on. You promised.”

“He asked me about your chair and it spilled out.”

“That doesn’t just spill out! Are you ever going to realize I’m an adult?” That could have been heard outside the hut, despite the lack of air.

I cleared my throat. “Can you keep your voice—”

“Why? Why would I do that? You don’t keep your mouth shut when you should.”

I kept my voice level. “We can talk about this later when you’re—”

“When I’m what? Rational? Calm? When no one’s in earshot to hear what a shitty person you are?”

I left. I went where she couldn’t go: downstairs.

“Fine! Run away from the scary women in a chair!”

The hut used to be the maintenance hangar, and below ground were equipment storage workrooms. Most of the old stuff had been salvaged when it was permanently shut down a century ago. What remained became the Eagle replica. I closed an emergency pressure door that still read, in faded red stencil, BAY 2: ENGINES. The metal-on-metal clank quieted the yelling from above. If Petrus was a good man, a brave man, he would come in and comfort her. If not, she was the one scaring him away, not me.

The sofa down there looked about as ancient as the bones of Buzz Aldrin. It somehow still smelled of oil and fuel. I lay down heavily on the old thing. If it wasn’t for me, Eva would probably still be crawling around that damn commune. The ones in charge didn’t look to have anything wrong with them. Eva made little sculptures to help support the place. “Everyone does what they can,” she explained. Why the hell would someone buy merchandise from an organization that does the opposite of good? That’s not the way she saw it, though.

After I had tracked her down after her mother died in a shuttle accident, she refused to leave with me. She was “with her people.” Damn cult. We’d been mending bones for millennia, printing organs for centuries, what the hell was wrong with extending medical care to gene therapy? Too often I didn’t understand this generation.

At dinner that night, I slipped something into her wine, which made her agreeable to a train ride, me pushing her in that manual wheelchair contraption. The dosing kept her giggly and woozy so she would enjoy the trip with no resistance, as we had to switch lines twice. She was pissed as hell when she sobered up and realized that we were halfway across Luna at this old hut. The place was a mess, but I had it safely pressurized. When she calmed down, she listened to my proposal: I would get her an autochair and a job. She agreed to a strictly temporary deal. If she still hated everything after six months, I would buy her a ticket back to her old looney-ass commune.

Eva found some purpose in helping an old man with his wild dream of rebuilding the Eagle, of performing shows about the first lunar landing. Three months in she was sculpting stylized 20th century astronauts as merchandise. A whole year had passed and she never mentioned going back to the commune. She still clung to her convictions, but she seemed happy enough here.

As much as I would have loved to see her walk, I knew better than to suggest any gene treatment. Ever.

“Suffering has been banished. Is that good? Is it?” Eva’s voice came through a little mic I’d planted in her bedroom. I sat on that old sofa downstairs, my ear bud receiving wirelessly. “The struggle, the struggle to survive, something that’s written into our genes has been erased. And look what happens. The less work we have to do to survive, the less pain we endure, the more we commit suicide. You think that’s just a weird correlation?”

I knew this mic business was a little assholish, but I needed to know what Petrus was up to. And if Eva was all right. She’s not exactly very open with me.

“But…you can’t walk.” That was Petrus, voice gentle. Smooth con work.

“Well, that’s the point, isn’t it? I suffer and struggle in an uncaring universe. And it’s good for me. Millions of years of evolution programmed us for suffering and survival. How many teens are out there right now cutting themselves, burning themselves, all because they aren’t allowed to suffer what nature throws at them?”

After a pause of Petrus digesting that crap, he replied, “But is the problem a lack of suffering? Not a lack of purpose, or of belonging, or—”

“Sure, all of these things contribute. I’m not saying this is the only factor. But making life so easy and comfortable…it’s inhuman; our minds aren’t equipped to deal. Where there isn’t suffering, we’ll make some. Or kill ourselves.”

I was dozing off as she went on and on. But my ears perked when my subconscious noticed the subject switch to me.

“He was sort of pitiful. He retired from decades of ground transport maintenance, wasn’t successful at community theatre, and started getting into everyone’s business. You know, old lonely people stuff. Talk about a loss of purpose. When mom died, he sort of lost it and came to see me. He freaked, like I knew he would. Gramp never listens, he’s one of those old guys that thinks he knows everything and gives unwanted advice.”

Petrus chuckled. “I see that.”

That stung. The wisdom of bugging her bedroom grew dubious. But I couldn’t turn it off, either.

“He told me about this abandoned place and how he managed to get it livable. He’s a good fix-it guy. Then he started on about his new dream: making the Eagle replica. Now, you’ve seen the thing, worked inside and out of it. Looks pretty good, right?”

“Impressive.”

“Sure. But back when he was telling me about it, along with antique spacesuits and a show, I believed he was losing his mind. Someone would tell him to get treatment, maybe gene-related, but I wouldn’t let someone do that to him. I would have to care for him, right?”

“You’re kind.”

“He’s my Gramp.” I heard the bed shifting, maybe Eva propping herself up. “I had to go back with him, make sure he wasn’t going to hurt himself. He was thrilled, I helped out where I could and, well, we pulled it off. Everyone was so happy I was helping him. He stopped messaging them all a dozen times a day.”

They laughed again.

Fine. If she wants to spin the tale to make herself look like a hero, so be it. For a minute there I thought she might tell him she had built everything herself as I stayed here on the downstairs sofa babbling like a senile idiot.

“He’s okay, seems sharp enough,” said Petrus. “He’s pretty protective of you.”

“Like I don’t know. But, that’s part of what keeps him spry and alive, acting as my protector.”

Come on. Like where would my legless granddaughter be without me? I left the recording mode on and yanked out my ear bud.

Petrus and I stood in the airlock. Quite a bit of dust had accumulated in the corners and I was about to tell him to do a sweep, as I cleaned the inner visor of my helmet with a microfiber cloth.

“Mora, close the door,” said Eva to the house angel as she blew a kiss to Petrus as the door slid closed.

Petrus held up a hand as I brought up my helmet. “Hold up.” He turned off the mic on the wall, the comm link with Eva. His eyes narrowed. “I found that transmitter you put in Eva’s bedroom.”

“What are you—”

“Don’t even try any stories with me. Have you been listening to us make love, dirty old man?”

“No. That’s not why—” His smile made me stop. It was that easy to catch me. I seethed inside, how could I be so stupid?

“Okay, then. Tell me.”

I felt a rigid scowl creasing my face. “I’m suspicious of you. I want to make sure Eva’s okay.”

“Well, is she?”

“She’s fine.” I pulled the helmet over my head, banging the neck ring.

I could still hear him. “You still suspicious of me? Think I mean Eva some harm? Am I a bad guy?”

I couldn’t look him in the eye. “It doesn’t look that way.”

“My thirty days are about up. How about we call a truce?”

“Did you tell Eva about this?”

“I wanted to talk with you first.”

I nodded. “Fine. Truce.”

When I stepped groggily into the living room the next morning, there was no humming autochair, no laughter, no cooking scents.

A note was stuck to the inner airlock door: “You’re sick. You need help. I can’t take it anymore.”

Eva was a little prone to extremes, but what was she talking about? I pulled the note down with an achy hand, walked into the kitchen where the monitor was live with the view of the bed in Eva’s room.

My heart caught.

A year ago Eva had caught a particularly nasty, antibiotic-resistant flu strain. So sick, so weak, she couldn’t get herself to her chair or to the bathroom. I tried sleeping on her floor, but sometimes she would have these bouts of delirium and she would scream at me until I left. I thought the solution of a hidden camera worked rather well. She recovered, I forgot about it. When I set up the mic recently to spy on Petrus, it must have connected the forgotten camera…the feed recording to Mora, just like the mic. Recording all activity.

Day and night.

Oh, fuck me.

Now I looked like a spying pervert.

I had Mora ping Eva. As expected, no answer. I tried Petrus, same result.

I rushed to the equipment vestibule to climb into my tightsuit. They must have headed to the port. But from there, where? Back to that goddamn commune? Did Petrus fall for that shit?

No tightsuit. Why would they take mine? It hit me: to sell. We don’t have much money, but a tightsuit in great working condition was always in demand. I had to use the damn bloatsuit. And surely they took off in the buggy. Since the train to the ruins didn’t run on Tuesdays I was essentially trapped here, at least for the day. Nice work, Eva. She’d even convinced Petrus to ditch his gig.

Trapped, and soon, penniless. And far worse: forever bereft of my granddaughter. Maybe I could deal with loneliness. But with the eternal hate of Eva?

It was 8:19. A five-kilometer hike separated me from the port.

I had to do it.

The process of donning and checking the antique suit solo was going to be a serious pain in the ass. Thermals first, no medical monitoring crap. As I wrestled on the outer torso, I asked Mora for the day’s train schedule. One at 9:55, another at 12:20. If they had made the 9:55 I was screwed. She might be gone forever. My heart ached at the notion.

When I clicked the helmet on and pressurized, it was already 9:35. Against all logic I skipped the checklist. If something went wrong out there and I died alone in the lunar dust, that was a fate better than losing Eva without making an all-out effort.

I had a five-kilometer run to the port, maybe two hours. Upping the O2, I cycled through the airlock and followed the buggy tracks, shuffling the lunar hop, kicking up the gray dust, sun to my back casting a long shadow forward. I was glad it was day.

To my right stood the ruins that everyone came to see, a lone traffic control tower beside the hotel and terminal that was Luna’s first commercial spaceport. The tower stared blankly at the landing zone, her windows long ago broken by vandals and scrappers. The octagonal hotel stood alone without a sleeping guest for over a hundred years, its red bricks 3D-printed from the dust and dyed with colorant expensively shipped from Earth. Grand times, then, when the solar system had become accessible to the common man.

The ruins slipped behind me. Growing on the horizon were the lights of Port New Cairo. The glowing thrust of a large moonhop dropped slowly, its engines arresting its descent until it rested gently on the apron.

The last kilometer left me panting, my own breath loud in my ears and partially fogging my helmet. The folks at the main terminal know me and waved me through the foot-traffic airlock. Here I receive all our deliveries once or twice a month. I removed my helmet and gulped the air not sullied with my own stink. I considered running in with the bloatsuit still on, but security would stop me and check over everything. Slowly. I had so little time, but I set to work removing the old suit as quickly as I could by myself. It was tough. And maddening. My thermals were soaked with sweat; my thinning hair clung wetly to my scalp. It didn’t matter how I looked, as long as I didn’t scare security.

Farouk knew me, and I was glad to see a friendly face at the train security gate. “Are you okay, Guy? Should I call a med tech?”

“Can you let me in?” My breathing had yet to normalize. “Emergency. My granddaughter is about to leave.”

“Let me screen you first, then off you go. And what are you wearing?”

I stood in the blue and white cylinder as I was scanned for weapons and explosives and dangerous micro-mech. There was never a longer ten seconds in my life.

Free, I ran through the concourse. A blinking screen warned that the 12:20 was boarding. The peach-colored bird nest architecture soared twenty meters above; faded photos of old Port Armstrong lined the walls, zipping by as I raced. I slowed as I spotted them: Petrus pushing Eva in her chair. Pushing. Something was wrong.

“Hey,” I said, coming up from behind. “Wait.”

Eva saw me, her eyes hardening in anger and hurt. “We’re leaving, Gramp. Go home.”

Petrus stopped pushing.

“Eva…Eva.” Being out of breath wasn’t helping. “A minute? Please? I didn’t mean to record the video. That camera was there when you had the flu.”

“Petrus, keep me rolling.” She turned away from me, her jaw set, that vein in her temple pulsing.

He nodded and maneuvered her toward the pressurized train hangar, GATE 3. Carrying their duffels and purses, people hurried around us to board.

I walked alongside them; I explained what had happened. It sounded like bullshit. Who would believe a sleazy, low-rent tourist trap man pleading in his sweat-soaked thermals? No one. Not even his granddaughter.

“Let me take a look at the chair before you board. At least that, okay?”

Petrus bent to whisper to her, but I could still hear. “Let him do it. I don’t know how.”

“Fine,” she spat. “You got five minutes before we have to be on that thing.”

Petrus said, “Let me run up to the desk, explain the chair situation.” He jogged off.

I knelt and popped the back panel, exposing the wiring and the rear of the battery. “I shouldn’t have done it, Eva. I shouldn’t, okay? I was suspicious of Petrus, and I’m sorry. You really think I was watching you? I wasn’t. I mean…I—I don’t know what to say.”

“You’re a nosy, suspicious old man,” she hissed. “There’s no way but your way. Ever. Maybe you weren’t being a perverted Peeping Tom, I don’t know for sure. But I’m leaving. If I don’t leave now, I might never. I’m not happy here.”

“What am I going to do? You’re my heart.” I replaced the back panel, issue resolved, and I stood with legs shaky from the run. “All I ever wanted was for you to be happy, to get fixed—”

“There’s nothing wrong with me!” she shouted. Reflexively, she grabbed the stick controller for the chair, and its sudden lurch surprised her. Eva rolled away. Away from me.

Petrus strode up to her, looked back to me, and mouthed the words, “Thank you.” He turned to walk alongside her through the open sliding doors, into the train, and out of my life.

I turned, shoulders slumped, headed slowly and purposelessly back toward home. I’d recharge the O2, maybe grab a meal…no, I wasn’t hungry.

I sat on a bench at the door to the foot-traffic airlock, suited up, helmet beside me, tuning out the chatty couple asking about the antique suit. I didn’t answer them. I couldn’t even hear them. Then they left, too.

In my hands was the autochair’s problem. It was a disrupter I’d installed on the battery, designed to cut the power if she ever went far enough from the hut to lose the beacon signal. If she ever tried to get back to that Purist cult.

If she ever tried to leave me.

END

Leave A Comment