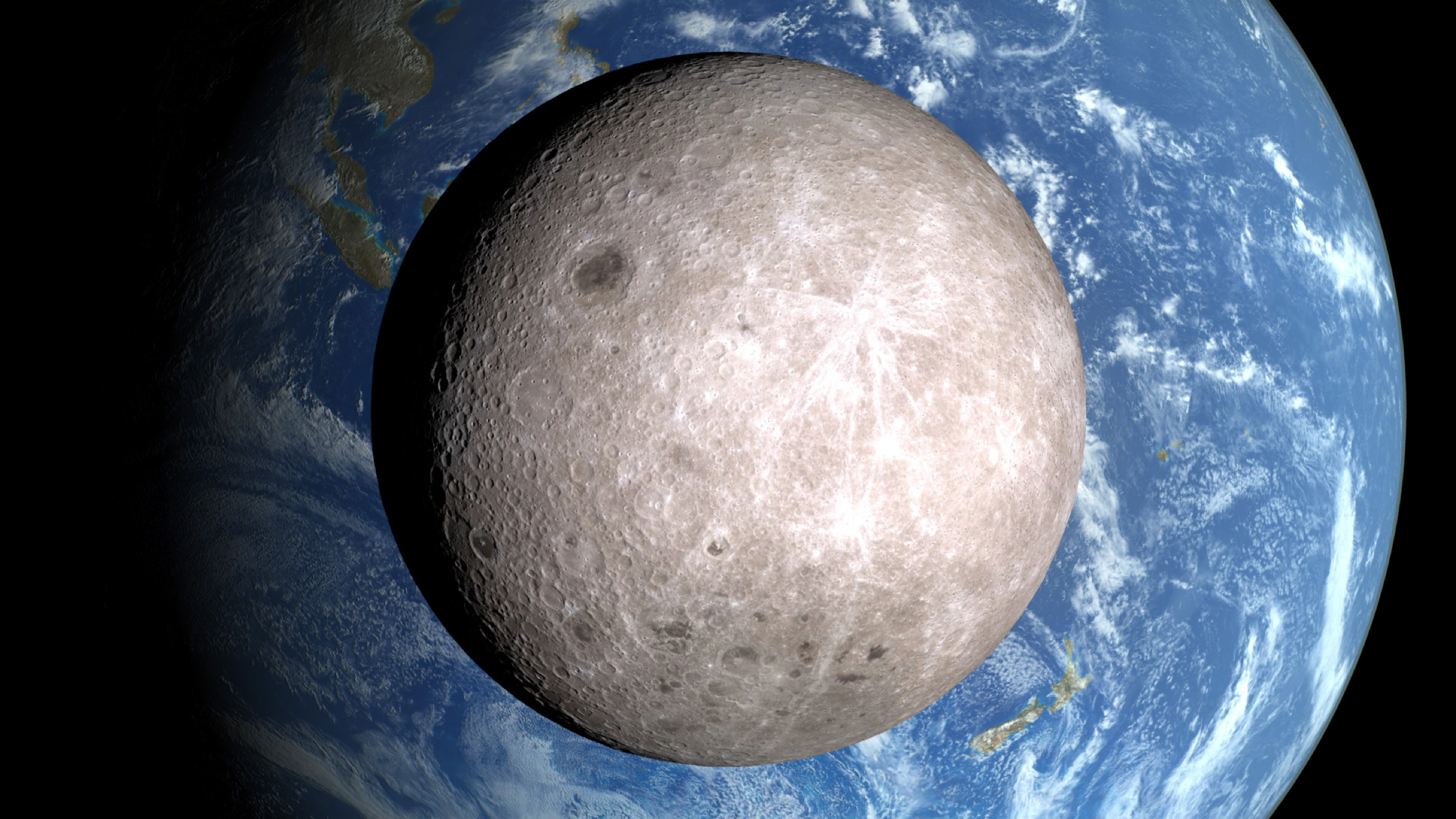

Image courtesy of NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio

Rosalee

by Katie Boyer

My sister wives and brother husbands

She flexes her toes in new high-heeled shoes, feels the press of Earth gravity on her body for one last day, discomfort in the balls of her feet. Her parents’ simple church is festooned with ivy and daffodils, the air fresh with morning rain and glittering with sunlight. Leandro’s voice rings caramel rich and still unfamiliar as he speaks the words, holding her hands. Today he serves as groom and officiant both, though he sways subtly, like a tall pine on a lazy day, his wheelchair close by to receive him. Faces of various shades and ages, people she has never met, watch and smile from the monitor screens set up hurriedly around the altar. The faces belong to his husbands and wives. To her husbands and wives.

we are gathered here

Like gawkers at a freak show. The pews are laden with onlookers, more crowded than she has ever seen them. A handful of acquaintances from high school or college or nursing school have come, along with most members of the small congregation, dressed in spring colors and skeptical expressions. Few young children stir among them; permits from the population authority have been difficult to obtain the last few years. On her back she feels an itch where her older brothers and childless sisters-in-law have fixed their eyes. All are present to witness her marriage into a Luna family, a line of six living spouses and three departed ones, progenitors of fifty moon-born babies. Many in the audience have never seen a man as gravity-changed as Leandro. Some have gathered for the novelty, perhaps, but no doubt most attend to critique her choice: to leave her father months before the cancer claims him; to take his investment in her education and fly it into the sky. Yet her dying father, white-haired and silent, is the only one who looks at her with anything like pride.

in the light of almighty Sol

She is hardly a fundamentalist, but her Bible is coming with her, its stories and poems as familiar as her mother’s face. Leandro made only a single comment about the weight of the tome with its gilded pages and underlined passages—every ounce costs rocket fuel, he said—but he has not objected to her Christian attachments as such. He did insist, if someone so jovial can be called insistent, that they use Luna’s vows for the ceremony, speak the same words that have bound the line of husbands and wives. But he told her she could also pray to her own God if she wished. For him, only the sun is all-powerful. From that star radiates energy for the stations in Terra’s orbit, fuel for the rovers on Luna’s dusty soil, heat for the dwellings beneath the surface, where the colony thrives. Only Sol conducts the true symphony of planetary movement, he believes, and lesser gods, even the Christian one, must find their place in the dance.

to declare this woman

Rachel, Leah, Bilhah, Zilpah: four wives of Jacob, wedded through bargain and jealousy and deceit, through hard work and trade, the mothers of twelve strong sons. David, king of Israel, married eight times or more, his son King Solomon rich with seven hundred wives and three hundred concubines. All those alliances, that concentration of wealth. At least she will be Leandro’s partner rather than his property. She may be marrying four women and two men, but the God of the Bible Himself has been more imaginative with human husbandry than to insist families always be built from a single pair of opposite-sexed mates. These are the things she said to her parents on the night of her engagement. Her mother left a half-chopped cabbage on the cutting board and crossed the kitchen to slap her face.

one with our family.

Lunatic. Subject to periodic insanity, controlled from afar, like the tides, by changes in the moon. Her brothers have long suspected her of a kind of madness. As a child, she’d watched the far-away cloud and fire of the first Colony rocket arc up from the Cape and, seeing that wonder, ran between rows of her father’s soy crop, arms extended over the low, tightly-packed leaves, wishing that she, too, could fly. She has fed goats with her brothers, trailed them across fields in her rubber boots, been the constantly-questioning kid sister. She has snapped beans and shelled peas, sliced okra to be breaded and fried, but she has never wanted their ordinary life. Always she has needed to break beyond the fields, to crack open the sky, to look into things that cannot be seen. With her medical training, twice the education of either farm-hand sibling, she understands her father’s cancer. She pictures his pancreas, the organs of his body close, the spread of wild-grown cells to his kidneys and stomach, little colonies sent through the bloodstream into his brain. She will not be present to see his limbs wither or his skin yellow. He will be dead by the time she returns to Earth to choose her own spouse to join their line, folded into the ground that he has cultivated.

She will share our flesh and our labor

Aloft, on a dry and airless world, she knows how the lower gravity will alter her body. She has seen it in patients at the clinic, seen it in Leandro. Her vertebrae will drift apart, adding inches to her height and straining the muscles in her back. Her heart, accustomed to fighting the gravity of Earth to pump blood upwards, will push more fluid than she needs into her torso, swelling her face and arms, and her legs will grow as thin and weak as Leandro’s. But so many things will be new and exciting, so many will be easier. She will have the strength to move huge and massive containers, to work in their home and their hydroponics compartments, to provide medicine for those who grow ill. The strength to consummate their marriage separately with all her spouses, to offer herself to each according to their individual wishes. She represses a shudder. The oldest ones are frail, Leandro has told her, and will not ask much.

our breath and our drink

Does she love Leandro? She loves his playfulness, the dance of light in his eyes and the hints of sadness at the edge of his smile. In videos, she has seen what he is like when free from pain. They move so gracefully there, at home on Luna, each gesture part of a dance, toys and pots and pans coasting through the air, released from the constant weight of worry that has kept her family so solemn. Watching the videos, she can believe Leandro is the athlete he claims to be, not the easily-fatigued man she has known only a few weeks who finds anything heavier than a coffee mug difficult to lift. She believes that he is fond of her, feels proud that she of all Earth women is his choice, but she cannot completely silence the voice telling her she is just one more check on the cargo manifest, an item to be stacked alongside the hammered aluminum and seeds and drill bits. One Terran wife, mostly healthy, carefully packed and prepared for shipment.

our shelter and sustenance.

Less than a month ago, she did not know Leandro. She knew that a Luna man had been in their clinic for bone density tests. She had caught glimpses of his dark hair as his wheelchair turned a corner, heard his voice down the corridor, her mind bristling with questions. Then one day, she opened the door to the exam room, and there he was. It was so easy to talk with him, so easy to accept when he asked to meet. A twilight evening in the Botanical Gardens, a turn around her parents’ fields, and the offer was extended and accepted, sealed with nothing more strenuous than a kiss. It had been just as sudden for him, he said, when Keyonna came to Brazil. Keyonna had thought she wouldn’t find a spouse that trip, feared she had failed the family, but then she’d met him, at work in the wildlife preserve where she had come to purchase snakes for propagation. He had left everything to go up with her and her cargo, to father children and manage serpentine livestock. Rosalee feels certain that she, too, will prove herself. She works with plants as easily as with medicine. It is the babies that frighten her; she has never held an infant.

Her children shall be ours and ours shall be hers

Someone sneezes in the audience and, from the odd places in her memory, she remembers a joke about the moon being made of cheese. She imagines Leandro and his family burrowing through it like so many mice, gnawing tunnels and lining their nests. Her grandparents refused to believe the weather patterns of their planet could shift, did not accept that the world could change and send them back to the farms their great-grandparents had tried to leave behind. Her grandchildren will never set foot on Earth, will be too well adapted to Luna to survive in Terran gravity. They will never know this humble church with its dusty pews or see a daffodil that has not grown in a nutrient bath. Her children are not yet conceived, and already she has changed their destinies. Already she has given them to strangers.

for as long as this line shall last.

For a moment she does not realize it is over. There is no Amen. But then Leandro is kissing her, leaning on her, pressing his weight as well as hers into her toes. She returns the kiss with real heat, feels his hand tighten briefly at her waist. Then their lips part and she helps lower him into his wheelchair. He covers her hand on his shoulder with his hand, and they move down the aisle. Soon well-wishers and the merely curious press around them at the reception, drawing them apart. She sips the iced tea someone has handed her and, half listening to a friend of her mother’s, she imagines how it will be tomorrow on the rocket up from the Cape. She thinks of President Kennedy. We choose to go the moon, he said, a hundred years ago, and still his name graces the launch sites. She has never even been on an airplane, wonders vaguely if she’ll be sick. Flight suit instead of wedding dress, fire at her back and oxygen ready, a thousand ways she could die. Then Leandro beckons from across the room, his eyes bright like the stars that guided ancient explorers across oceans, and she pushes smiling toward him through the crowd. She does not look back.

Katie Boyer

Leave A Comment