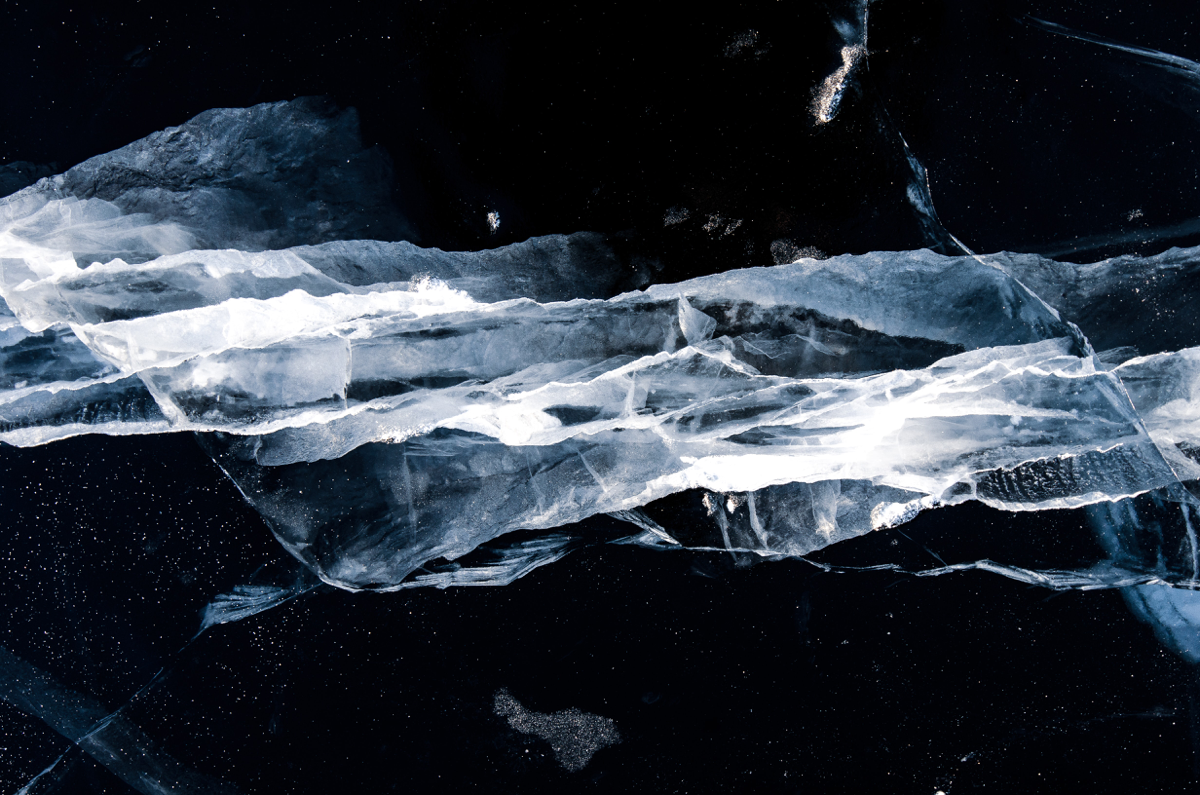

Image by Daniil Silantev

Harmonies of an Icy Moon

by John Park

It was Nic’s idea for the three of them to go down to the dims after class. They were in the corridor of the upper level, sharing the last of a stand-up lunch before their engineering class, and the lights had just pulsed for noon.

“It’ll be easy. I’ve got the lock codes and I can turn off the eyes.” Down the corridor a crew was setting up to respray the walls. Nic kept his voice down, though the stale, aromatic rush from the air vent behind him would mask his words.

Usually Ratch came up with their plans, though Stef had once led them through the forbidden maze of the hydroponics chamber where her mother worked. We share everything, the three told each other. It wasn’t quite true, but it gave Nic enough reason to speak. He wondered if this would be the day to tell her about the music he was writing. He was still trying to find a bearable way to approach the topic.

“Down there, Nicko?” asked Ratch. “Nothing down there but bare walls. My old man used to check on the seals, before he went to Minerals.”

“Ghosts maybe,” said Stef. “Dad says there’s noise from there on the geophones sometimes.” She wore the blue jumpsuit Nic secretly liked; she had pulled her hair back and pinned a crimson airchid blossom over her ear.

“But no one’s died in the dims,” he said carefully. “No one’s lived down there – that’s the point. They bored the space out and never used it.”

“Why you want to go down there now?” asked Ratch. He looked quickly at Nic. “Things okay?”

“Gotta take over my dad’s job next month. The flash came today.” He didn’t add that he had been waiting for that flash for the past week, from the day they put his father’s body in the recycler. “Might not get another chance.”

“They’re not sending you up to the surface, Nic?” Stef asked, her voice tense.

“No, it’s okay. Going to get his old job, they said. My dad wouldn’t have been switched up there if he hadn’t asked.” He pushed on, answering Ratch, before the memories could get painful. “I was down there in the dims once, before they closed it off. With him. Something I need to do there.”

Stef nudged Ratch and said, “Right, Nic. Let’s chase some spooks.”

Ratch bent his knees and pushed off from the floor, his eyes closed, frowning. At the ceiling he lifted both hands and shoved against the pitted blue insulation.

“All right,” he said as he came down. “We put my uncle’s entry pass into the wall where he’d worked, after they took his body for the ‘cycler.” He gave a crooked smile. “Still touch the place when I’m there. Let’s do the dims.”

“We’ll need our lights,” Stef said. “What else?”

“Gloves and cold rations. It’s not insulated, but the water-main to Sector Five runs through it, and that stops it freezing too hard.”

“You can kill the eyes for sure?” asked Ratch.

“Yeah, my dad, he . . .” he began, but then the entrance slid open and the magistra in her black suit stood waiting for them with three hours of finite-element analysis.

At the square metal door, Ratch looked back quickly at a monitoring eye and asked, “You got the blinders and the codes from your dad? They still good?”

“We’re here, aren’t we? And no one’s come after us.”

Nic pulled out his comm, went to the lock control, opened the panel. “I pulled the codes out of his comm before they took it back. He did them new last month. Showed me how to get them . . . ” He stopped as his throat started to tighten.

The telltales stayed green when Stef pushed the lock open, and they drifted through.

They came into a tunnel extending to left and right. When Nic closed the lock behind them, only the bluish beams of their ledlights glistened over the bare white walls, free of pebbly, blue-sprayed insulation, of lights and notices and warning signs, of surreptitious, finger-sized graffiti, and small watching eyes.

The space was empty apart from a water duct fastened along the angle of wall and floor. The cold air smelled white and empty, too, making his face and chest ache. In each direction the corridor faded into darkness.

Their breath started to form clouds around them, like memories of the ones who had bored out this tunnel.

“The air’s good?” Ratch asked. His voice rasped into the silence.

“It’s okay. The end seals aren’t tight, there’s still some exchange with the upper corridors, and there’s nothing in here to turn it bad.”

Stef took a couple of bouncing steps off to the right. She pirouetted. “So where are the ghosts?”

“Further in, maybe,” Nic said, watching her move in her blue jumpsuit. “There’s another level down from here somewhere. They could be waiting for us down below.”

She laughed over her shoulder as she floated down. “Hiding from us, you mean.” The airchid petals curved like slow wings above her ear.

Yes, Nic thought, watching: Three-four time, and a change in harmony at the fourth bar…

Stef stopped, her light jerking over the walls. “What was that?”

“What?” Ratch started towards her. Nic followed.

“Creaking sound,” she said. “That way. From below, maybe. I couldn’t tell.”

Nic could suddenly hear nothing over his heartbeats. Then words poured out in a rush. “I was thinking. You know how the transducers work. Tides squeeze us. First this way then this. Like a pair of hands.” He had Stef’s attention. “There’s so much force, it gives us enough power for lights and everything. Nothing seems to move – only, of course, the crust – the walls, the floors and ceilings – they’re all moving, in and out, up and down, and that’s what these sounds are. That’s all. They’re everywhere, but now it’s quiet enough to hear them.” Stef was starting to look patient rather than interested. “But – but the reason that those hands can squeeze us as much as they do, is because, at the core, this world, down deep under the ice where we live . . . ” She turned as Ratch came over, and Nic fell silent.

“Can’t hear anything while you’re talking, Nicko.”

Her eyes flicked back to Nic. “It’s all right, Ratch,” she said, a bit too kindly.

Nic swallowed and pointed down the corridor. “The pipe goes up through the ceiling somewhere there. There’ll be a joint, a pressure sensor. . . .”

Stef looked into the shadows. She exhaled, nodded. “Could be shifting, leaking.”

“Why don’t you go and check it out? There’s a drop shaft back this way. Went there that time with my dad. I’ll go there for a bit.” Down there, his father had said, and It’s secret. “I’ll be all right. If I hear anything I’ll call you.”

Ratch nodded and launched himself to the ceiling. Nic watched him float down and Stef walk to his side. He turned away and moved into the shadows. Ahead of him his light found the roped-off opening of the drop shaft.

He stopped, remembering the time he had come with his father and carved his name and the name of where they lived into the wall. He turned and shone his lamp up and down. And found it, just below his waist height. “EUropa,” with his name above it. The words glistened, the edges of the incisions softer now, the last five letters of the world’s name awkward and childlike, smaller than his hand, the first letter firm and strong – his father’s correction, added with a quick smile afterwards.

At the time Nic had resented being taken away from his synthesizer, which he had almost trained to produce three-part harmony, and he had barely spoken.

His throat tightened again. This would be bad. He switched his light off.

And inevitably that memory brought the recent one: his father in the hospital, lying grey-faced and hairless among a tangle of tubes and wires, his eyes bloodshot in their hollows. The smell of vomit under the disinfectant.

“Nic? That you?” A thick, clotted whisper. “Got caught when a megastorm hit. Rad-meter off-scale, and the lock door jammed.” His father blinked and shook his head. “You know that, sorry. Shouldn’t have taken the job. But I’d promised . . . ” His father let his head slump back onto the pillow and gasped quietly. Nick wanted to ask him what promise had been worth getting on the surface crew, but before he could find the words his father looked at him hard and said, “What time is it? Shouldn’t you be in . . . ?” He broke off again and closed his eyes for a few moments, breathing heavily. “Never mind. It’s good you made it, Nic,” With an effort he lifted his head again. “I’ve something for you. Don’t tell anyone. . . .”

In the dark corridor, Nic doubled forward, pressing his forehead against the wall, his eyes squeezed shut, his wrist jammed into his mouth to stifle the sounds he made.

When the worst was over, he still trembled. It was cold here, below the insulated corridors full of light and people. Stef was worried about him, he knew that. He should have told her and Ratch what he was doing. He stood up, wiping his sleeve across his eyes. It wasn’t too late. Look, he could say, there’s something my dad found. It’s a secret. But we share everything, right? He turned back to follow them.

Ratch had set his lamp on the floor so that its light reflected off the ceiling and walls. Nic saw that Ratch had removed his glove and was pressing his palm against the wall. Something made Nic leave his light off and stop.

Ratch brought his hand down, flexing his fingers to warm them. He took Stef’s lamp and held it to the wall so its light struck along the surface. His hand had left its print in the ice.

Stef went close. She removed her own glove and put her hand up, first below his, then, after a moment, into the place where his palm had been. Her fingers fitted into the impressions his had made.

She turned and looked at Ratch, her eyes wide and steady. As Nic watched, the look on her face changed. It turned into one he had never seen but instantly understood. Ratch looked back at her. They gazed at each other as though they were the only humans in the world.

Nic couldn’t breathe. He backed away. His chest felt as if it had been kicked. He stumbled back through the dark until he brushed against the ropes around the drop-shaft. He stepped over them and let himself fall.

He hit bottom before he expected to and slumped against an icy wall, his pulse throbbing in his skull and his breathing ragged. Blue suit, he thought. Flower. That look. Idiot. Idiot. He slammed the heel of his hand against the hidden wall, jarring his wrist bones, then froze as the flat thud reminded him where he was.

After a few moments he switched on his light and peered about him.

He was crouching near the end wall of the corridor – a jagged ice-face riven by splits and fractures. The ladder he remembered had grown lumpy encrustations of ice. Before him his breath made a half-visible curtain, opening and closing. The back of his throat burned. He closed his mouth, tried to swallow.

Something ticked.

He turned the light up, swung it wavering across the end wall. Ice gleamed; cracks and inclusions glistened. Had one of those cracks changed? He held his breath to listen.

Tick.

In the wall beside him, a crack lengthened by perhaps the length of his finger. Three fragments like tiny crystal wings split away and drifted to the floor.

He aimed the light at the tip of the crack, turned the intensity up full. His hand was shaking so much, the ice seemed to churn and shiver. He had to peer from the side to avoid the worst of the reflections, try to make sense of the play of light and dark.

In the depths of the ice, one of the shadows shifted.

He could see no face, no eye, but he was certain it watched.

He couldn’t tell what he felt, even whether he was afraid. All his feelings seemed to have been squeezed into a hard icy ball just below his heart.

You’re real.

He was unsure whether he had actually whispered the words.

You’re still here.

His light quivered; the ice flickered without motion.

He swallowed and raised his voice a little. “I’ve brought you what he promised.” His voice rasped into the silence.

He lifted the comm, thumbed the control to start the replay, and pressed the glowing face to the ice.

This is it, he said silently. What he went out there to get for you.

As the scene played into the ice; he remembered what it showed: five figures wearing vacuum suits, in bright primary colours, seen from his father’s viewpoint. The others moved across a greyish space without walls – a wide, damaged-looking floor, littered with fragments. And no ceiling – just blackness overhead. The lighting was low and pale; it threw long shadows beside the figures. Then the viewpoint pivoted and a sector of banded disc hung over the horizon. It seemed to fill half the sky. Two round dots of shadow marked its surface, and then the viewpoint shifted again, canted upward to find among the darkness above, first one, then two, tiny gibbous lights. They began to swell in the field of view.

In the bottom-left corner of the images, among the numbers and icons of the bio-data, a warning stick of yellow light suddenly extended upward. The viewpoint returned to the surface. It began jerking, lurching forward, and he saw the other suited figures turn and stumble across the rubbled ground. The stick of light turned orange, then red. It began to flash, and the recording ended.

That’s all he could get, Nic thought. You wanted the images, not the suit’s record, the – outside. But did you understand those numbers, those symbols at the end – pulse, breathing, the rest? Can you read what he was feeling then? He’s dead. Do you know what that means? Those signs showed the processes happening in his living body. And those processes have stopped, because of what he did for you. They’ve stopped forever, understand? There’ll be no more of those particular data. Ever again. . . .

Nic closed his eyes. Where is he now? Can you tell me that?

He slid down until he sat on the floor, his shoulders against the ice.

He pulled off his glove and reached up, pressed his fingertips to the ice where his comm had been. The cold flowed into his flesh.

He opened his eyes and stared at the wall of ice. Do you know what I feel?

It would hurt for a while, and then all feeling would fade away. He wondered what would replace the numbness.

I can’t go back up there.

A silent convulsion spread through his mind, as when a handful of meal was slipped into water about to boil.

Maestoso. The archaic term broke into his thoughts. Massive. Minor key. Falling bass (more bass, more bass), glittering syncopations above –

For an instant he saw, quite clearly and unmistakably, a vast dark space without floor or ceiling or wall, in which dashes and globes of light flickered and great looping strands that coiled and stretched. . . .

He remembered the magistra showing them images from the oceans of a forgotten world. One of the creatures there had eight arms like a nest of cables and a beak like a pair of bolt-cutters; it was said to squeeze itself through any space larger than that beak. . . .

Struggling to fit such an image around those shadows in the ice, Nic had a sudden visceral sense of what it would mean – to climb by wedging himself into crevices, squeezing upwards through cracks and weak spots, driving his body up through tunnels he had to force open with his own flesh, fighting pressure and gravity every instant, and always alone.

And at the end – to discover those strange forked upright creatures that tottered about on twin spines of flesh, and ventured into the unimaginable spaces above the world. . . .

Nic pulled his hand away from the wall, and there was just the light. The glistening ice showed the marks his fingers had made. His hand still burned and throbbed.

What had happened today was scored into his memory. Like the words and the handprints in the ice, it would blur but remain, would mark him even after he had outgrown it.

And one day, too, all this would be as strange to him as it must be to the creature in the ice. Even his father dying among the wires and machines. Even Stef and Ratch.

And he’d known, hadn’t he, how it would have gone if he had played Stef the music he had made for her. She would have listened and said it was nice, given him a smile and changed the subject. (And the slow middle section in the relative major – why, why, why had he used that?)

“Hey, Nicko,” Ratch called. “The pipe’s good. You still down there?”

Nic cleared his throat. “Thought I heard something.” His voice sounded strained. “Weird echoes down here. Probably just the ice shifting. Focused echoes, that’s all.”

He got up and started towards the ladder. The hard icy knot was still in his chest. He was safe as long as he could hold it there, stop it bursting open and splintering. . . .

He stopped and looked back at the blank wall.

I’ll come back when I can. I’ll find a way to get more images.

He turned to the ladder and pulled himself up

We’ll talk. We’ll find out how to create music together. We’ll share everything.

END

Leave A Comment