Photo by Immo Wegmann

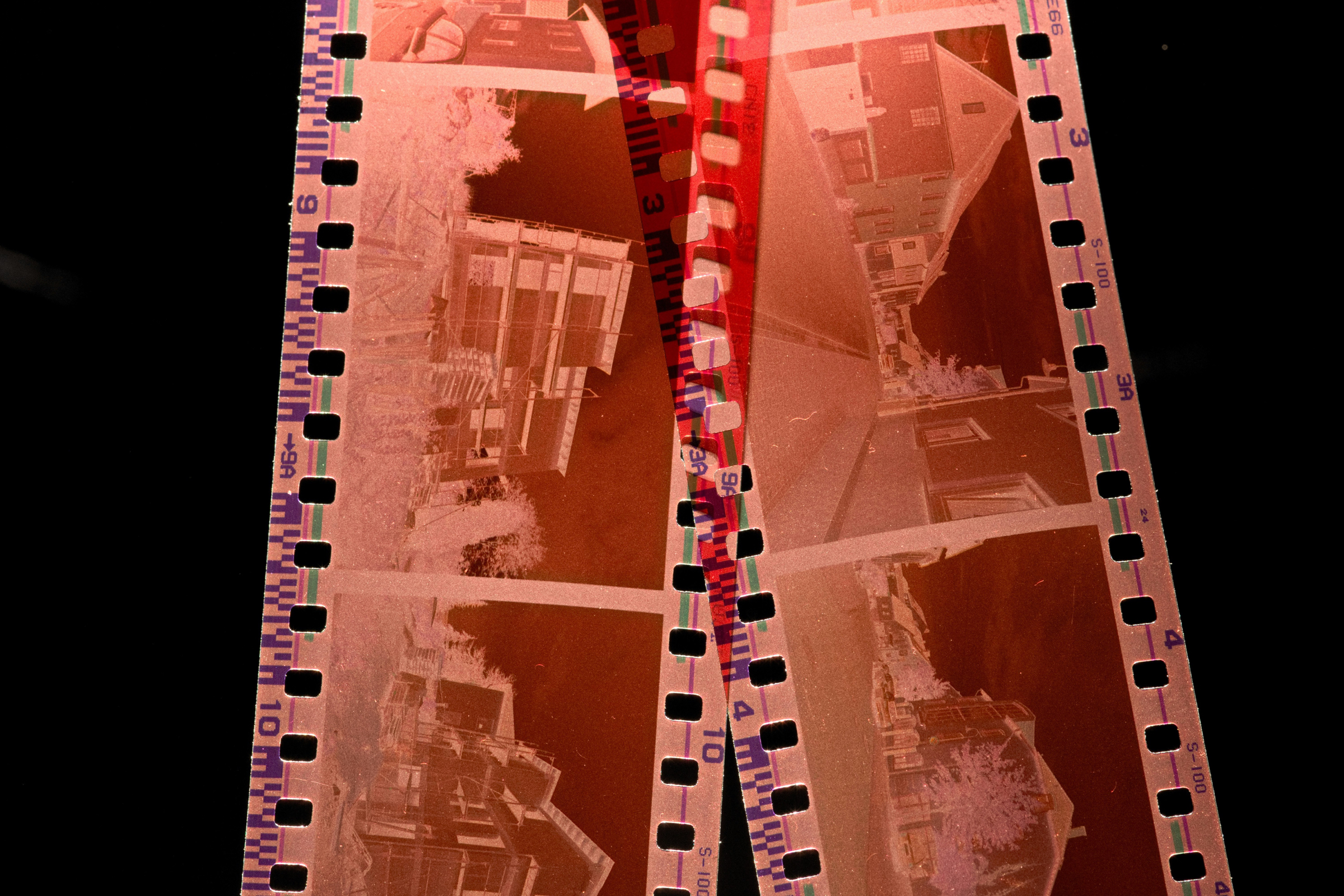

Afterimage

by Kathleen Schaefer

Two days after he died, the photo of my neighbor vanished. It had hung on my wall for years, right above the bowl where I kept my keys. I’d stopped seeing it ages ago, glancing over these permanent fixtures as if they would always exist. Like I could always check tomorrow what color shirt he was wearing.

To the best of my recollection, which already grows fuzzy and unreliable, the photo showed us sitting on his porch sipping some violently turquoise drink. He’d always order two bottles of the strangest sodas he could find, saving one for me because only I was brave enough to try them. They always tasted terrible. That one, an over-sweetened version of that childhood flavor best described as blue, was no exception.

Now the picture frame had gone blank, the image replaced with an icon prompting me to select a new photo. My thoughts didn’t go straight to Deletion—a choice too absurd and extreme for an innocuous soda-drinking neighbor—but when I searched for a new picture, every single photo of us had been removed from my private storage.

Until he died and subsequently wiped all traces of himself from digital existence, I had no interest in my neighbor’s history beyond the nostalgias of high school baseball and college parties that we swapped over sodas. Now I spent hours trying to search for his name on the internet, hoping the AI trawlers had missed some crucial bit of data in their purge. There was nothing. In the absence of information, my imagination crafted unsavory histories, the kinds of stories he’d make sure would die with him. I left the picture frame blank.

I’d seen the warnings to keep duplicate physical copies of everything, back when debates over Right To Be Deleted laws played out on billboards and ballots. I’d printed out a couple family photos, shoved them in a box, then forgot about it all. The laws got signed, and it wasn’t the doomsday scenario detractors predicted. We granted the government expansive rights to let their AIs trawl even our most private databases, and then we kept on living. The things they actually deleted—non-consensual pornography, leaked addresses, exposed social security numbers—no sane person would argue against. Yes, there were court cases, even a prominent activist who claimed the trawlers removed entire years’ worth of valuable data without cause. But it didn’t affect us everyday citizens.

As for the last clause, the right to have all personal data permanently removed upon death, it barely mustered a single protest. Opt-in only, so it’d never get triggered. Not by normal people, at least.

Working from memory, I sketched the photo on the back of an old envelope to test my own recollection. I’d seen that picture yesterday, yet I couldn’t even say with certainty which side of the porch he sat on. I set the pencil down before my neighbor grew into anything more than a detail-less outline. That act seemed more intrusive than searching his name: here I was, trying to recreate someone whose final wish had been to disappear. I tossed the sketch into the recycling, shuddered like I’d burned the man’s last remaining image, then fished it back out. Creating it may have been unethical, but destroying it was heretical. I folded the envelope and tucked it into my pocket.

His daughter drove past his house three times before stopping.

“So this is the right place,” she said when I waved from my yard before walking over to join her. “I was stupid enough to keep his address stored in my phone. Didn’t think they’d wipe that, too. Maybe this is all punishment for not visiting enough to memorize the street. But I knew it was around here even if I didn’t remember the exact spot. Just drove around, searching for anything that looked familiar.”

“Do you know why he did it?” The moment I asked, the question felt taboo.

“No. He didn’t even tell me he was going to. I guess that’s common. People are afraid that the moment they publicize their choice, everyone will start printing photos and searching their name. You know, uncovering all the things they want deleted. I would have.”

She beckoned me over and we sat on the same porch that was no longer featured in my no longer existent photo.

“A part of me wants to reach out to every person he’s ever known and stitch his life back together, bit by bit,” she said.

“Then do it.”

“He doesn’t want that. And how would I document it all, anyway? I can’t even write an obituary without trawlers deleting the file the moment they see his name. The only final respect I can give my father is to forget him.”

Perhaps this whole affair was a cruel performance art. That through Deletion, he made this non-existence into his legacy. Where there once was a man, there existed only his absence, but that absence was a thing as concrete as the person himself. When we talked about him, we only talked about his disappearance. It was a conversation on his terms.

“And the forgetting happens so fast,” she said. “I can’t remember the way he parted his hair. Whenever he got my voice mail, he’d always ask what crazy party I was at that was more exciting than a phone call from Dad. I saved those recordings, expecting everything to be preserved. I never wanted to lose his voice. He took that from me.”

“Then take it back. Write it down on paper if you have to. A litany of every beautiful or bland fact about him.”

“Just turn him into a list?”

“Every dead person is a list. A resume of accomplishments, a few two-dimensional photographs, some highlight moments—but even those are half-constructed by an imperfect memory.”

“Exactly what he chose to delete.”

He had chosen to confine his memory to whatever recollections we held in our heads, untainted by photographs and videos. To avoid the preserved image of a person eclipsing the actuality of who they were, even if that condemned him to the rapid deterioration of human remembrance. I’d spent these last days agonizing over the why of that choice, whether it was to bury an unsavory past or control the inaccessible future. But now his daughter sat before me, facing the impossible task of both remembering and forgetting her father. The why of it all didn’t matter.

“Your memories are for you, not him.”

I extracted the creased envelope from my pocket, and despite all my worrying about fading recollections, she recognized the thin sketch of a portrait immediately.

“I didn’t know he let you drink his sodas.”

“He had awful taste in sodas. Here, start your list with that one.” I flipped over the envelope and handed her a pen.

She grinned. “We used to drink them together.”

“Bet he still has some. Want to raid his fridge? I’ve got the spare key.”

“Yes, please.”

She wasn’t ready to enter the house, so I went through the refrigerator alone. The scent of decaying vegetables and spoiled dairy assaulted my nose, but the bottom shelf was all soda, arranged in prismatic order. I grabbed two bottles of a green-tinted orange liquid. He’d mentioned these a couple months ago, saying he nabbed some discontinued orange mint spice soda. Even I wasn’t brave enough to try that. But now we were toasting to his memory. Or the end of his memory. Either way, the drink felt appropriate.

I carried the bottles to the porch and cracked them open for the two of us. The drink, predictably, was vile.

On the back of my sketch, she began her list:

- Could always find the best tasting sodas

With those scribbled words, untouched by the AI trawlers, she recreated her father’s memory, not as he was, but as he was to her.

She visited again, a couple years later, and asked me to complete the sketch I’d drawn of him. I’d taken down the empty picture frame, deeming its contents irreplaceable, but when she handed me a pencil, I drew him from memory without hesitation.

Her list had grown to a full notebook with some memorials in bullet points and some in long, winding entries. Like all memories, it was flawed, biased, a simplified projection of a full human. But what Deletion had removed, she replaced with a version of her father that was exquisitely her own. I set my recreated photo beside it, two imperfect memories side by side.

Existing.

END

Leave A Comment